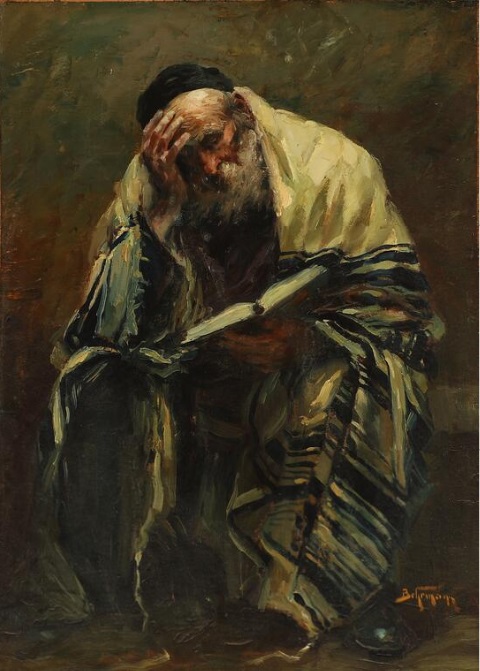

Featured Art: “Abraham Adolf Behrman, A Reading Rabbi “

Many Christians have argued that the Talmud discusses Jesus in a polemical manner. Several passages in the Talmud seem to suggest that Jesus was a false prophet or a heretical figure, and these claims have been widely debated. In this post, I want to explore these Talmudic references, offering insights from both the Jewish and Christian perspectives. Understanding the Talmud’s treatment of Jesus and related figures is best achieved by considering the Jewish context and the authority of the rabbis who composed it. After all, the Talmud is sacred Jewish literature, and interpreting its references requires an awareness of the rabbinic tradition and the historical backdrop of the texts.

Before delving into these discussions, it’s important to clarify that the Talmud is not a single book, nor is it simply a collection of books. Rather, it is more accurately described as a vast library—a massive compilation of Jewish law, theology, debates, and interpretations that spans centuries of rabbinic scholarship.

First, we must recognize that the period immediately following the destruction of the Second Temple (70 CE) was one of intense religious and cultural conflict. For the first five centuries after this event, polemical writings were not uncommon—on both sides of the Christian-Jewish divide. These kinds of theological arguments, critiques, and counter-arguments were pervasive throughout early Christianity. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that we find evidence of disagreements and critiques between Jews and Christians in the Talmud. This was, in many ways, just as common in the ancient world as it is today.

There are multiple theories surrounding the Talmudic narratives about figures such as Mary, Balaam, and Yesh”u (Jesus). What do these stories really mean, and how should we understand them? To explore these questions, let’s consider each point more closely.

Who Is Balaam?

Some Christians and even scholars have argued that “Balaam” in the Talmud is a “codeword” for Jesus.

This idea stems from various passages in the Talmud that describe Balaam negatively and connect him to sorcery or immoral behavior. However, many rabbinic scholars reject this interpretation, asserting that Balaam is simply the biblical figure from Numbers 22-24, and in no way a codeword for Jesus. In the book “Jesus in the Talmud” by Peter Schäfer, he writes the following excerpt:

“In Mishna Sanhedrin x, 2, we read: “Three kings and four private men have no part in the world to come. The three kings are Jeroboam, Ahab and Manasseh. . . . the four private men are Balaam, Doeg, Ahitophel and Gehazi.” This passage belongs to the famous chapter ofthe Mishna, entitled Chelek, because it commences by saying that “all Israel have part(chelek) in the world to come,” and then enumerates the exceptions. The three kings, Jero-boam, Ahab and Manasseh are all mentioned inthe Old Testament as having introduced idolatry, perverted the true religion. The immediate connection of the four private persons arouses the onjecture that they were condemned for the same offense. This conclusion is strengthened by the fact that the preceding paragraph of the Mishna (x, 1) in this chapter excepts from theprivilege of the world to come according to Rabbi Akiba also such a person “who reads in external books and who whispers over a wound,and says, None of the diseases which I sent in Egypt will I lay upon thee, I the Lord am thy healer.” Now the external books, according tothe Gemara upon this passage are the Siphre Minim, i. e., the books of the Jewish Christians or Christians generally, which books by way of caricature Rabbi Me’ir ( 130-160 A. D.) calls awen gillayon (literally, margin of evil) and Rabbi Jochanan (Me’ir’s contemporary) calls azvon gillayon (i. e., blank paper of sin) —thus in Talmud Shabbath 116a (MS. Munich). The words ”who whispers over a wound, re- fer to the miraculous cures of the Christians.”

Peter Schafer makes the argument that Balaam is a type of Christ, stating the following:

“It is evident that Balaam here does not mean the ancient prophet of Numbers 22, but someone else for whom that ancient prophet could serve as a type. From the Jewish point of view there was considerable likeness between Balaam and Jesus. Both had led the people astray; and if the former had tempted them to gross immorality, the latter, according to the Rabbis, had Tempted them to gross apostasy.

Schafer continues with his stance in his book by quoting Sanhedrin 106b:2 from the Talmud, In the Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 106b we read thus:

“A certain heretic (min) said to Rabbi Hanina,’Have you ever heard how old Balaam was?’ Hereplied, ‘There is nothing written about it. But”Judas Iscariot would answer to Doeg the Edomite,who betrayed David (1 Sam. xxii. 9). 34 since it is said, Bloodthirsty and deceitful men shall not live out half their days (Ps. lv. 23), he was either thirty-three or thirty-four years old.’ He (the heretic) said, ‘Thou hast spoken well, I have seen the chronicle of Balaam in which it is said, Balaam, the lame, was thirty-three years old when the robber Phinchas killed him.’ “

He goes on to raise the point that Rabbi Hanina lived at Sepphoris and died in 232 AD. There seems to be no apparent reason why a Christian should have asked him as to the age of the ancient Balaam. While Balaam does have its similarities to Jesus, especially being the age of 33 or 34 at the time of his death, or the similarities between the names Pilate and Pinehas , being the ones who kill the figure, I still think this position is flawed. The William Davidson Talmud explains this more in-depth stating the following in Sanhedrin 106b:2

“A certain heretic said to Rabbi Ḥanina: Have you heard how old Balaam was when he died? Rabbi Ḥanina said to him: It is not written explicitly in the Torah. But from the fact that it is written: “Bloody and deceitful men shall not live half their days” (Psalms 55:24), this indicates that he was thirty-three or thirty-four years old, less than half the standard seventy-year lifespan. The heretic said to him: You have spoken well, I myself saw the notebook of Balaam and it was written therein: Balaam the lame was thirty-two years old when Pinehas the highwayman killed him.”

Why This Typology is Inherently Christian

Schafer’s arguments are interesting, however, I would argue it is not supported by mainstream scholarship, which tends to emphasize that Balaam in the Talmud is not associated with Jesus, and any such connection is anachronistic or speculative, drawn from later Christian readings or reinterpretations rather than from the rabbinic tradition itself.

In the Encyclopedia Judaica, the majority of historians assert that the passage in question likely does NOT refer to Jesus. The idea that Balaam is a type of Christ, I will admit, is more of a Christian interpretation, and not a typical reading in Jewish tradition. Therefore I would say the connection of Balaam’s age to Jesus, and the comparison of Pinehas to Pilate, seem more like speculative interpretations that were influenced by Christian ideas, rather than reflective of traditional Jewish teachings or Talmudic exegesis.

How Does the Talmud Insult the Mother of Jesus?

If we entertain the premise that Balaam is a type of Jesus, and we look at the parallels drawn in Sanhedrin 106b, we must still wrestle with the passage that alludes to a woman “playing the harlot with carpenters” in the previous portion of the passage, (106a). The argument goes like this: if Balaam is a veiled reference to Jesus, then the mention of a woman having a relationship with carpenters must somehow point to Mary. After all, Joseph, Jesus’s earthly father, is often described as a carpenter. This line of reasoning relies heavily on symbolism and eisegesis, or reading meaning into the text that is not explicitly there.

However, I think it’s important to consider the broader context and be cautious about making such connections. The tradition of Balaam’s descent, which some claim parallels Jesus’s story, appears in sources like the Tanchuma (Balak 5) and the Yalkut Shimoni (Numbers 771), but even then, these texts do not directly link Balaam with Mary, let alone with Jesus himself.

The Talmudic passage from Sanhedrin 106a states the following:

“It is stated: ‘And Balaam, son of Beor, the diviner, did the children of Israel slay with the sword among the rest of their slain’ (Joshua 13:22). The Gemara asks: Was he a diviner? He is a prophet. Rabbi Yoḥanan says: Initially he was a prophet, but ultimately, he lost his capacity for prophecy and remained merely a diviner. Rav Pappa says that this is in accordance with the adage that people say: This woman was descended from princes and rulers, and was licentious with carpenters.”

While it is tempting for some to interpret the phrase “playing the harlot with carpenters” as a veiled reference to Mary, who is the mother of Jesus and Joseph’s wife, such an interpretation seems highly speculative. The Talmud itself does not draw this explicit connection, and one would need to engage in a considerable amount of eisegesis—reading a specific interpretation into the text—rather than relying on the text’s own clear meaning. In fact, the Talmud’s vagueness in this passage makes it difficult to confidently assert that it is referring to Mary or Jesus.

Personally, I do not take the position that Balaam is anything other than the ancient biblical figure known for his role in the Book of Numbers. While it is true that early Jewish traditions occasionally draw connections between figures like Balaam and later Christian themes, these interpretations are not straightforward, and there is little textual evidence to support the claim that Balaam is a direct reference to Jesus. In my view, the interpretation of Sanhedrin 106b as an indirect reference to Mary seems forced, and the Talmudic text itself DOES NOT support such a reading.

*Another text has been eluded to Jesus Christ, and his mother in that of, Shabbat 104b. This passage refers to a “ben Stada” which some scholars infer could be about Jesus of Nazareth, and oddly enough, Sefaria includes this passage under the context of the passages that seem to infer the of Jesus. The passage mentions an interpretation that identifies Ben Stada with Jesus. This suggestion is all based on the allusion to Pandira and strengthened by the mention of a Passover execution and of a mother named Miriam (Mary). This is a very confusing passage, claiming there is a woman named Miriam Megadla Se’ar Nashaya (מִרְיָם מְגַדְּלָא שְׂעַר נְשַׁיָּא) which can be interpreted as “Miriam, who grew the hair of women,” which is understood as a reference to her being a hairdresser or beautician who took care of women’s hair. Some speculate this “Miram Megadla” sounds like the “Mary Magdeline”, in the Bible. One could see how maybe the Rabbis confused Mary Magdeline to be the mother of Jesus, but I think that is entirely speculative. However as convincing as it may seem, I think it is still a stretch to definitively assume this is Jesus and His Mother. You can read more about this subject from another apologist work titled “Jesus In The Rabbinic Traditions” here.

Why Balaam Can’t Be Jesus Christ

There are many issues with typing Balaam to be Jesus Christ but one of the most prominent is a very disturbing passage from Gittin 57a

“Onkelos then went and raised Balaam from the grave through necromancy. He said to him: Who is most important in that world where you are now? Balaam said to him: The Jewish people. Onkelos asked him: Should I then attach myself to them here in this world? Balaam said to him: You shall not seek their peace or their welfare all the days (see Deuteronomy 23:7). Onkelos said to him: What is the punishment of that man, a euphemism for Balaam himself, in the next world? Balaam said to him: He is cooked in boiling semen, as he caused Israel to engage in licentious behavior with the daughters of Moab.”

Here we can see a disturbing passage about Balaam being “cooked in boiling semen ” for his sin of leading Israel to immorality. However this cannot be about Jesus for reasons stated in the the previous portion of this article, there is just nothing to pull from the text and you have to read Jesus into the narrative. But the strongest argument why Balaam cannot be Jesus is because he is mentioned in the very next section under the name “Yeshu HaNotzri” in Hebrew which translates to Jesus the Nazarene.

In the next section of Gittin 57a: 3-4 we see the following,

“Onkelos then went and raised Jesus the Nazarene from the grave through necromancy. Onkelos said to him: Who is most important in that world where you are now? Jesus said to him: The Jewish people. Onkelos asked him: Should I then attach myself to them in this world? Jesus said to him: Their welfare you shall seek, their misfortune you shall not seek, for anyone who touches them is regarded as if he were touching the apple of his eye (see Zechariah 2:12). Onkelos said to him: What is the punishment of that man, a euphemism for Jesus himself, in the next world? Jesus said to him: He is punished with boiling excrement. As the Master said: Anyone who mocks the words of the Sages will be sentenced to boiling excrement. And this was his sin, as he mocked the words of the Sages. The Gemara comments: Come and see the difference between the sinners of Israel and the prophets of the nations of the world. As Balaam, who was a prophet, wished Israel harm, whereas Jesus the Nazarene, who was a Jewish sinner, sought their well-being.”

The imagery of being punished by “boiling in excrement” fits with a polemical portrayal of figures like Jesus. The severity of the punishment would align with Jewish perceptions of Jesus as a false prophet who led people astray, which is how many Jews during late antiquity saw him. While I find it compelling to interpret the Talmudic figure “Yeshu the Nazarene” as Jesus Christ, this opinion is not universally accepted. Rabbi Gil Student makes this argument in his blog for Jews for Judaism. He states the following about Gittin 57a,

” Interestingly, if someone were to claim that Yeshu in the passage above is Jesus, then Balaam cannot also refer to Jesus because both Balaam and Yeshu are in the passage together. In other words, it is self-contradicting to claim that the passages above about Balaam’s mother being a harlot or dying young refer to Jesus and to claim that the passage above about Yeshu being punished also refers to Jesus. You can’t have it both ways.”

What Does Yeshu Mean?

While the talmud is vague about the subject and scholars have often pondered, it could be a reference to the name of Jesus, Yehsua.

“Yeshu”, coincidentally is also an acronym for a curse: “yimakh shemo ve zikhro” which means, “May his name and memory be obliterated”.

Yeshu is made of three Hebrew letters – Y-Sh-U (ישו), but it is missing the last letter of his name – the “Ah” sound.

This last letter is called an “Ayin” (ע), which, rather interestingly, means “eye”. It’s almost as if without the “ayin” one is unable to see, but when the “ayin” is added, sight returns to the blind.

In any sense, it is not clear what Yeshu means. We don’t know.

However, we have a good idea of who it refers to.

Why Yeshu Is Most Likely Jesus Christ

In the Talmud, we see many references to the figure Yeshu. The Name “Yeshu ha-Notsri” meaning Yeshu the Nazarene is noted in Sanhedrin 107b. It’s interesting to mention as well, Sefaria has a portion of their website that includes a text and source sheet for the name Jesus. In this list, we see many references to this Yeshu figure, who they seem to claim is named Jesus.

The term “Yeshu” was likely used in many medieval polemical texts to refer to Jesus, particularly in anti-Christian writings. While Yeshu can sometimes be ambiguous, it becomes a more specific identification when combined with the term “Nazarene”, which clearly refers to Jesus of Nazareth. I believe it’s important not to overlook this detail. As I’ve mentioned previously, polemical writing was common during the early centuries of the Common Era, and it often led to extreme actions, including mass burnings by the church. For instance, on June 17, 1242, the Disputation of Paris took place, which resulted in the destruction of nearly 10,000 copies of the Talmud and other Jewish sacred texts. Similar events occurred throughout history, particularly in the 16th century and beyond. As a result, much of what we know about the original Talmudic texts is somewhat unclear.

Historically, sections of the Talmud were censored by Christian authorities due to their perceived anti-Christian content. In many editions, the name “Yeshu” was either altered or entirely removed to avoid conflict with Christian teachings. This censorship meant that the identification of Yeshu with Jesus, was obscured in some versions of the text but resurfaced in uncensored versions, suggesting that earlier rabbis understood the reference to be Jesus.

This brings us to the Hesronot Ha-Shas, a collection known for documenting the “missing” or “censored” parts of the Talmud. In these texts, we find references to figures that seem to represent Jesus, though these references remain indirect, cryptic, and subject to interpretation. The Hesronot Ha-Shas helps illuminate the original Talmudic language before Christian censorship altered them, indicating that some early rabbinic writings did indeed refer to Jesus Christ, albeit in veiled terms. As Christianity distanced itself from Judaism over time, Jewish communities responded with defensive or critical writings, including stories that portrayed Jesus negatively.

Before Jesus: Is The Talmud’s “Yeshu” a Different Person?

I previously stated that Rabbi Gil Student mentioned that Yeshu most likely refers to a 1st-century BC leader who deviated from rabbinic teachings. This narrative is found in the Sanhedrin 107b and almost the exact thing recorded in Sota 47a where it states:

” The Sages taught: Always have the left hand drive sinners away and the right draw them near, so that the sinner will not totally despair of atonement. This is unlike Elisha, who pushed away Gehazi with his two hands and caused him to lose his share in the World-to-Come, and unlike Yehoshua ben Peraḥya, who pushed away Jesus the Nazarene with his two hands.”

In this narrative, the Jewish idea of not pushing someone away with two hands is a symbolic way of saying always have one hand free to allow them to be pulled back in, however in this instance it is clear Jesus the Nazarene was fully pushed away from Yehoshua ben Peraḥya. The narrative then says Further in the passage we see,

“What is the incident involving Yehoshua ben Peraḥya? The Gemara relates: When King Yannai was killing the Sages, Yehoshua ben Peraḥya and Jesus, his student, went to Alexandria of Egypt. When there was peace between King Yannai and the Sages, Shimon ben Shataḥ sent a message to Yehoshua ben Peraḥya: From me, Jerusalem, the holy city, to you, Alexandria of Egypt: My sister, my husband is located among you and I sit desolate. The head of the Sages of Israel is out of the country and Jerusalem requires his return.”

“Yehoshua ben Peraḥya understood the message, arose, came, and happened to arrive at a certain inn on the way to Jerusalem. They treated him with great honor. Yehoshua ben Peraḥya said: How beautiful is this inn. Jesus, his student, said to him: But my teacher, the eyes of the innkeeper’s wife are narrow [terutot]. Yehoshua ben Peraḥya said to him: Wicked one! Do you involve yourself with regard to that matter, the appearance of a married woman? He produced four hundred shofarot and ostracized him.”

“Jesus came before Yehoshua ben Peraḥya several times and said to him: Accept our, i.e., my, repentance. Yehoshua ben Peraḥya took no notice of him. One day Yehoshua ben Peraḥya was reciting Shema and Jesus came before him with the same request. Yehoshua ben Peraḥya intended to accept his request, and signaled him with his hand to wait until he completed his prayer. Jesus did not understand the signal and thought: He is driving me away. He went and stood a brick upright to serve as an idol and he bowed to it. Yehoshua ben Peraḥya then said to Jesus: Repent. Jesus said to him: This is the tradition that I received from you: Whoever sins and causes the masses to sin is not given the opportunity to repent. And the Master says: Jesus performed sorcery, incited Jews to engage in idolatry, and led Israel astray. Had Yehoshua ben Peraḥya not caused him to despair of atonement, he would not have taken the path of evil.”

Here we can see the pivotal moment comes when Yeshu, rejected by Yehoshua during his Shema prayer ( As seen in Deuteronomy 6:4–9, 11:13–21, and Numbers 15:37–41. The three portions are mentioned in the Mishnah (Berachot 2:2)), and he mistakenly believes he is being driven away. In despair, Yeshu turns to idolatry, symbolized by worshiping a brick, and leads others astray. This story is a polemical critique, portraying Yeshu (Jesus) as a figure who deviated from Jewish law and became a source of corruption for Israel, reflecting the Jewish community’s response to the rise of Christianity. All of this takes place in the first century BC.

So how do we find out who this Jesus is? It turns out this story has some similarites with the biblical Jeus. Peter Schafer asks this very question stating: “we have here again one of those striking anachronisms for which the Talmud is famous. The event under King Jannai (i. e., Alexander Jan- naeus) is historical.

After the capture of the stronghold Bethome King Jannai (104-78 B. C.) had 800 Pharisees crucified. This crucifixion was the occasion of the flight into Syria and Egypt on the part of the Pharisees generally in the country, and among them Joshua ben Perachjah and Judah ben Tabbai. The question may be asked, how did the name of Jesus come to be introduced into a story referring to a time so long before his own? Bearing in mind that the rabbis had extremely vague ideas of the chronology of past times, we may perhaps find the origin of the story in its Babylonian form in a desire to explain the connection of Jesus with Egypt.The connecting link may, perhaps, be found in the fact of a flight into Egypt to escape the anger of a king. This was known in regard to Joshua ben Perachjah, and the Gospel (Matt,ii. 13 et seq.) records a similar event in regard to Jesus. There may be some other details in the life of Jesus which the rabbis had in view when they remodeled the story to suit their purpose. Hence, in rejecting the date, it is not absolutely necessary to reject the whole of the Babylonian version as entirely devoid of every element of genuineness. Again, as to the lateness of the Babylonian version, it is to be observed that the Gemara quotes from an earlier source or tradition of the story, as can be seen from the closing words of the Talmud passage (Sanhcdrin 107b) given above.

Peter Schäfer addresses this chronological discrepancy by suggesting that the rabbis of the Talmud didn’t have the same historical precision we expect today. They were less concerned with strict timelines and more focused on thematic connections between events. Schäfer explains that the story of Joshua ben Perachya and his flight to Egypt could have been retrospectively applied to Jesus’s story in Mathew 2:13, where an angel of the Lord commands Joseph to escape to Egypt with Jesus, due to the shared motif of escaping royal wrath. In this way, the rabbis may have used stories from earlier times, such as the one involving Joshua, and adapted them to fit later theological contexts, like the life of Jesus. The Talmud is not necessarily trying to provide a precise historical record, but rather using symbolic narratives to convey moral and theological lessons. So, even if the chronology of these events is out of sync, the core themes—like the flight to Egypt—are what connect the stories, making the inclusion of Jesus in this context more about tradition and lesson than about historical accuracy.

Just as the canon debates in the Talmud reflect the ongoing Jewish discourse over what should be included in scripture, the story of Jesus’ flight to Egypt is true in its essence—it just might not have been recorded with the same historical exactness in certain texts. In the same way that the Talmud includes anachronisms and debates about Jewish law, which don’t necessarily match the exact historical record but reflect the intellectual and theological struggles of the time, the story of Jesus traveling to Egypt in the Talmud or other Jewish writings are tailored to a moral or theological lesson rather than a precise historical account. The debates and the core events are real; it’s the recording and the way they were adapted that may differ.**

In more modern discussions, figures like Rabbi Michael Skobac have proposed a view that mirrors certain Islamic perspectives—that Jesus was a Torah-observant Jew who came to serve only Israel. It was only his later followers and the Pauline narratives that took the somewhat odd Jewish, but still acceptable faith Jesus practiced, turning his message into a religion of idolatry and apostasy, later known as Christianity. You can find the video IS JESUS IN THE TALMUD? by Rabbi Michael Skobac here. I will mention this video several times in the following sections.

I find this to be the “meat and cheese” of the debate on the Yeshu subject, so I want to point to two positions on this. The first perspective that of Rabbi Michael Skobac takes is the same as Rabbi Gil Student, the stories in the Talmud are just out of sequence, they don’t coincide with the time of Jesus. I hope to have shown, why that position is not the case, if not keep reading.

Rabbi Skobac’s Arguments: The Talmud’s Teaching on Jesus and His Disciples

Another rabbinic text from Sanhedrin 43a also refers to Yeshu ha-Notsri in ways that clearly parallel elements of the Jesus narrative, such as his execution and alleged miracles. The Sanhedrin says the following:

“But isn’t it taught in a baraita: On Passover Eve they hung the corpse of Jesus the Nazarene after they killed him by way of stoning. And a crier went out before him for forty days, publicly proclaiming: Jesus the Nazarene is going out to be stoned because he practiced sorcery, incited people to idol worship, and led the Jewish people astray. Anyone who knows of a reason to acquit him should come forward and teach it on his behalf. And the court did not find a reason to acquit him, and so they stoned him and hung his corpse on Passover eve.”

These texts, when taken together, strengthen the identification of Yeshu with Jesus.

Peter Schäfer in his work “Jesus in the Talmud,” argues that the context, wording, and historical tensions between Judaism and early Christianity make the identification of Yeshu ha-Notsri with Jesus of Nazareth highly likely. Schäfer and others analyze these references as part of a broader rabbinic strategy to address the challenges posed by Christianity. Schafer writes the following:

“And it is tradition: On the eve of the Passover they hung Jeshu [the Nazarene]. And the crier went forth before him forty days (saying), ‘[Jeshu the Nazarene] goeth forth to be stoned, because he hath practiced magic20 and 20 It is certainly strange that Jesus was charged with having practiced magic, whereas magical skill was one of the qualifications necessary for a member of the Sanhedrin. Thus we read in treatise Sanhedrin 17a Rabbi Jochanan says, none were allowed to sit in the Sanhedrin, who were not men of stature, men of wisr dom, men- of good appearance, aged, skilled in magic, 39 deceived and led astray Israel. Any one whoknoweth aught in his favor, let him come anddeclare concerning him. And they found naughtin his favor. And they hung him on the eve of the Passover. Ulla said, ‘Would it be supposedthat [Jeshu the Nazarene] a revolutionary, hadaught in his favor?’ He was a deceiver, and the Merciful (i. e., God) hath said (Deut. xiii. 8),’Thou shalt not spare, neither shalt thou concealhim/ But it was different with [Jeshu the Nazarene], for he was near to the kingdom.’ “21

This passage seems eerily similar to that of the Jesus narrative, however, what do we make of the stoning passage? The gospels never elude to the fact that Jesus was stoned, and one could argue, that maybe this has something to do with John 19, “Then Pilate ordered Jesus to be brutally beaten with a whip of leather straps embedded with metal. However, Schafer makes another connection in his book, stating:

In this passage we are told that Jesus was hung.With this must be combined the evidence of the passages given in the former section that he was stoned. The connection between the two state ments is that Jesus was stoned, and his dead body then hung upon a cross. This is clear from the Mishna Sanhedrin vi. 4: “All who are stoned are hung, according to Rabbi Eliezer. The sages say, None is hung except the blasphemer and he who practices a false worship.” The corpse was hung to a cross or else to a single beam, of which one end rested on the ground, the other against a wall (same Mishnah). The Gospels, of course, say nothing about a stoning of Jesus, and the Talmudic tradition is probably an inference from the fact that he was known to have been hung. The inference would be further strengthened by the application of the text, Deut. xxi. 23, “He that is hanged is accursed of God,” a text which Paul had to disarm in reference to Jesus (Gal. iii. 13). The Talmud knows nothing of an execution of Jesus by the Romans, as modern Jews claim, but makes it wholly the act of the Jews.

The passage from the Sanhedrin regarding Yeshu and his five disciples is perplexing, and Rabbi Skobac addresses its oddities in his lecture. At the 39-minute mark, he points out, “This is obviously a very strange passage in the Talmud. First of all, if these are the followers of Yeshu, who was executed on the eve of Passover for witchcraft and leading Jews astray into idolatry, it’s hard to reconcile this with Christian scriptures. Yeshu didn’t have five disciples; he had twelve.”

Rabbi Skobac highlights the inconsistency between the Talmudic account and the familiar Christian portrayal of Jesus, noting that none of the names of Yeshu’s disciples match those of the twelve apostles, though “Mattai” might refer to Matthew. What Rabbi Skobac does at first is acknowledge that Yeshu in the Talmud seems to have lived much earlier than Jesus of Nazareth, however, he admits the key to understanding this passage is to see its polemic.

He raises the question, “Does this sound like a real court proceeding to you?” and suggests that the dialogue in the passage, with its back-and-forth arguments and wordplay based on biblical passages, is more of a theological or polemical discussion than an actual courtroom account. He admits that such a scenario is possible. He argues that the passage is not a complete historical record but a polemical narrative designed to make a theological point: that followers of Yeshu, if he truly practiced witchcraft and idolatry, should meet the same fate as their leader.

This story, with its exaggerated arguments and unrealistic exchanges, appears less as an accurate historical recounting and more as a rhetorical tool criticizing the figure of Yeshu and warning against his followers. Rabbi Skobac concludes that these Talmudic stories about Yeshu, who seems to have lived decades before Jesus, should be understood as part of the Jewish polemical response to the rise of Christianity rather than as factual history.

So it seems on one hand the Rabbi says the narratives in the Talmud are too early, but then opens the possibility that these may be polemical writings.

The second position Rabbi Skobac takes is that while the Talmudic passages may not be 100% accurate or precisely dated, the rabbis were still addressing what would eventually become Christianity. He explains this in the 59:00-minute mark of the video.He argues the Jews, In critiquing Christianity, they brought Jesus into these discussions, using him as a way to attack the movement they viewed as deviant or abhorrent. These stories may not be historical accounts, but rather polemical attempts to undermine what the rabbis considered the foundation of Christianity by targeting its founding father, Jesus. It should be noted, that Rabbi Skobac subscribes to the idea that Jesus was not the mere “founder of Christianity, but rather the foundling“. The Rabbi mentions a portion from Avodah Zarah 16b-17a , a tractate about idolatry, where if you reference the Hesronot Ha-Shas, we see the passage is about Jesus. The passage states:

The Sages taught: When Rabbi Eliezer was arrested and charged with heresy by the authorities, they brought him up to a tribunal to be judged. A certain judicial officer [hegemon] said to him: Why should an elder like you engage in these frivolous matters of heresy? Rabbi Eliezer said to him: The Judge is trusted by me to rule correctly. That officer thought that Rabbi Eliezer was speaking about him; but in fact he said this only in reference to his Father in Heaven. Rabbi Eliezer meant that he accepted God’s judgment, i.e., if he was charged he must have sinned to God in some manner. The officer said to him: Since you put your trust in me, you are acquitted [dimos]; you are exempt. When Rabbi Eliezer came home, his students entered to console him for being accused of heresy, which he took as a sign of sin, and he did not accept their words of consolation. Rabbi Akiva said to him: My teacher, allow me to say one matter from all of that which you taught me. Rabbi Eliezer said to him: Speak. Rabbi Akiva said to him: My teacher, perhaps some statement of heresy came before you and you derived pleasure from it, and because of this you were held responsible by Heaven. Rabbi Eliezer said to him: Akiva, you are right, as you have reminded me that once I was walking in the upper marketplace of Tzippori, and I found a man who was one of the students of Jesus the Nazarene, and his name was Ya’akov of Kefar Sekhanya. He said to me: It is written in your Torah: “You shall not bring the payment to a prostitute, or the price of a dog, into the house of the Lord your God” (Deuteronomy 23:19). What is the halakha: Is it permitted to make from the payment to a prostitute for services rendered a bathroom for a High Priest in the Temple? And I said nothing to him in response. He said to me: Jesus the Nazarene taught me the following: It is permitted, as derived from the verse: “For of the payment to a prostitute she has gathered them, and to the payment to a prostitute they shall return” (Micah 1:7). Since the coins came from a place of filth, let them go to a place of filth and be used to build a bathroom. And I derived pleasure from the statement, and due to this, I was arrested for heresy by the authorities, because I transgressed that which is written in the Torah:

In this Talmudic passage, Rabbi Eliezer, accused of heresy, is brought before a tribunal where he initially responds to his accuser by suggesting that he trusts God’s judgment. He is then let go. However, Rabbi Akiva later reminds him of a past conversation with a follower of Jesus, which may have led to his arrest. The follower had asked Rabbi Eliezer a provocative question about the permissibility of using money paid to a prostitute for building a bathroom in the Temple, a discussion based on Jesus’ teaching. Rabbi Eliezer admits that he derived pleasure from this heretical idea, which, in the eyes of the authorities, transgressed the Torah. Rabbi Skobac mentions how odd this story is, and theorizes the followers of Jesus, though initially Torah observant, introduced ideas that challenged traditional Jewish law. Rabbi Eliezer’s eventual realization that his enjoyment of the heretical statement led to his punishment serves as a reminder of the fine line between engaging with new ideas and transgressing established beliefs.

What Is The Conclusion?

- Balaam is most likely NOT Jesus. To highlight Rabbi Gil Students’ point, if someone were to claim that Yeshu in Gittin is Jesus, then Balaam cannot also refer to Jesus because both Balaam and Yeshu are in the passage together. You may argue they are both types pointing to Jesus but I think this is highly unlikely and that Balaam is the biblical character.

- Mary is probably NOT called a whore. Sanhedrin 106b refers to a woman who could be Mary, the mother of Jesus, but its about Balaam. In Shabbat 104b, the name “Ben Stada” is mentioned in connection with the figure of Yeshu (Jesus), but drawing a direct line between this figure and Mary is problematic and makes it seem speculative.

The Talmud confirms the following about Yeshu. Each of these matches the description of Jesus in the New Testament:

- Jesus was crucified on the eve of Passover.(Sanhedrin 43a)

- Jesus had at least five disciples(Sanhedrin 43a)

- Jesus Traveled to Egypt (Sanhedrin 107b, Sota 47a)

- Jesus practiced “sorcery”(Sanhedrin 107b, Sota 47a, and Sanhedrin 43a, Gittin 57a )

- Jesus’ teaching impressed one rabbi. (Avodah Zarah 16b-17a )

- Jesus taught the establishment of a new community of believers that transcended the boundaries of Jewish law.(Sanhedrin 107b, Sota 47a)