One of the most influential figures in the Book of Mormon is King Benjamin.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints describes him as such,

“King Benjamin was a prophet of God who ruled the land of Zarahemla. He worked hard to serve his people and teach them about God. With help from other prophets of God, Benjamin made Zarahemla a peaceful and safe place to live.”

In this article I want to highlight some of the aspects of King Benjamin’s speech, which can be found in the book of Mosiah chapters 2-5. I want to demonstrate how the aspects of the speech mirror Protestant revival sermons from the 19th century rather than an ancient Jewish document. I do this because I think this is a decent anachronism that directly challenges the historicity of The Book of Mormon.

A Speech Worth Reading

Before getting too far into this article, I encourage you to read King Benjamin’s speech for yourself. It offers many insightful teachings, such as this passage from Mosiah 3:17: “And moreover, I say unto you, that there shall be no other name given nor any other way nor means whereby salvation can come unto the children of men, only in and through the name of Christ, the Lord Omnipotent.”

While there are many aspects of the speech that I agree with, my focus in this article is on how it reflects key elements of 19th-century Protestant revival sermons—specifically those of the Second Great Awakening—aligning more closely with the time and place of Joseph Smith than with an ancient Jewish context.

Comparing King Benjamin’s Speech to 19th-Century Revivalism

In “An Insider’s View of Mormon Origins“ author and historian Grant Palmer highlights an account from The Memoir of Benjamin G. Paddock (specifically pages 177–184). I will reference these pages in the following analysis among other sources. Keep in my mind all the references I will be comparing to The Book of Mormon align with the same time Joseph Smith lived.

My primary focus here is to compare the thematic and stylistic elements found in accounts from the time of Joseph Smith—particularly those related to religious revivals—with those in the Book of Mormon, all while considering the historical context of the early 19th century.

Instead of following Palmer’s specific argument, I aim to take a broader approach by examining the content of the Book of Mormon itself and comparing it to various sources from Joseph Smith’s time. This will allow us to explore how the themes, stylistic choices, and ideas in the Book of Mormon align with those that were prevalent during the era, especially when viewed through the lens of contemporary religious movements.

Here is what we find.

Personal Salvation and Individual Accountability

Revival sermons during the 19th century focused heavily on repentance and a personal relationship with God.

For example, the Genesee Conference (c. 1826) recounts how sermons traced “the whole process of personal salvation, from its incipiency to its consummation in the world of light.” (Pg.180).

Similarly, King Benjamin’s address emphasizes humanity’s dependence on God, the necessity of repentance, and the transformative power of grace:

• “For behold, if the knowledge of the goodness of God at this time has awakened you to a sense of your nothingness… then I say, if ye have come to a knowledge of the goodness of God… ye will always rejoice, and be filled with the love of God” (Mosiah 4:5–12).

Emotional Appeals With Vivid Imagery

19th-century protestant revival sermons often used vivid, emotional rhetoric to stir the hearts of congregants. One preacher at the Genesee Conference, for example, prayed, “O God, hold thy servant together while for a moment he looks through the gates ajar into the New Jerusalem!” (pg.180). This language stirred deep emotion among the listeners, who often wept or trembled.

Similarly, King Benjamin describes humanity as “less than the dust of the earth” (Mosiah 4:2) and speaks of the joy of redemption as being “filled with the love of God” and experiencing “peace of conscience” (Mosiah 4:12–13).

Communal Covenant-Making

Revival sermons often culminated in calls for public commitment to Christ, leading to mass conversions or covenant renewals. The Genesee camp meeting reports, “Hundreds came forward; some said nearly every unconverted person on the ground.” (pg. 181) King Benjamin’s speech ends with a parallel moment, as the people collectively covenant to follow God:

“We are willing to enter into a covenant with our God to do his will, and to be obedient to his commandments in all things” (Mosiah 5:5).

Millennial Themes and Final Judgment

Protestant revivalism frequently focused on eschatological themes, warning of judgment and emphasizing readiness for Christ’s return. The Genesee account refers to sermons contemplating “the track of the believer… till he had entered the land of Beulah” and the final judgment. King Benjamin similarly warns his people of the consequences of sin, urging them to prepare for judgment and eternal life:

“The time shall come when they shall know that they cannot be saved; for there can be no man saved except his garments are washed white” (Mosiah 2:38).

Repetition of Messages

Both revival sermons and King Benjamin’s speech employ repetition and rhetorical appeals to emphasize their messages. The Genesee preachers are noted for their ability to stir emotion and spiritual reflection through structured, repeated phrases. Likewise, Benjamin frequently reiterates themes of humility, gratitude, and the necessity of repentance.

“Falling Down”

The phenomenon of people “falling down” under the influence of the Holy Spirit was common in 19th-century revivals. In Mosiah 4:1-2, King Benjamin’s audience falls to the ground after hearing his words, a scene that mirrors the emotional and physical reactions of people in revival meetings, where individuals would faint or fall under intense spiritual experiences.

Mosiah 4:1-2 describes the following

“And now, it came to pass that when king Benjamin had made an end of speaking the words which had been delivered unto him by the angel of the Lord, that he cast his eyes round about on the multitude, and behold they had fallen to the earth, for the fear of the Lord had come upon them.”

This part of The Book of Mormon is extremely protestant. See the following example from Barton Stones’s Memoir,

“The scene to me was new, and passing strange. It baffled description. Many, very many fell down, as men slain in battle, and continued for hours together in an apparently breathless and motionless state–sometimes for a few moments reviving, and exhibiting symptoms of life by a deep groan, or piercing shriek, or by a prayer for mercy most fervently uttered. After lying thus for hours, they obtained deliverance. The gloomy cloud, which had covered their faces, seemed gradually and visibly to disappear, and hope /65/ in smiles brightened into joy–they would rise shouting deliverance, and then would address the surrounding multitude in language truly eloquent and impressive. With astonishment did I hear men, women and children declaring the wonderful works of God, and the glorious mysteries of the gospel. Their appeals were solemn, heart-penetrating, bold and free. Under such addresses many others would fall down into the same state from which the speakers had just been delivered.” Source

Furthermore, the Autobiography of Rev. James B. Finley states the following about a similar revival,

“A strange supernatural power seemed to pervade the entire mass of mind there collected. At one time I saw at least 500, swept down in a moment as if a battery of a thousand guns had been opened upon them, and then immediately followed shrieks and shouts that rent the very heavens.” Source .

When we combine these accounts, the similarities to the scene in Mosiah become striking. The reactions of King Benjamin’s audience and those in the 19th-century revivals share the same emotional intensity and physical responses, providing further evidence of the anachronistic nature of the Book of Mormon and its reflection of 19th-century religious culture.

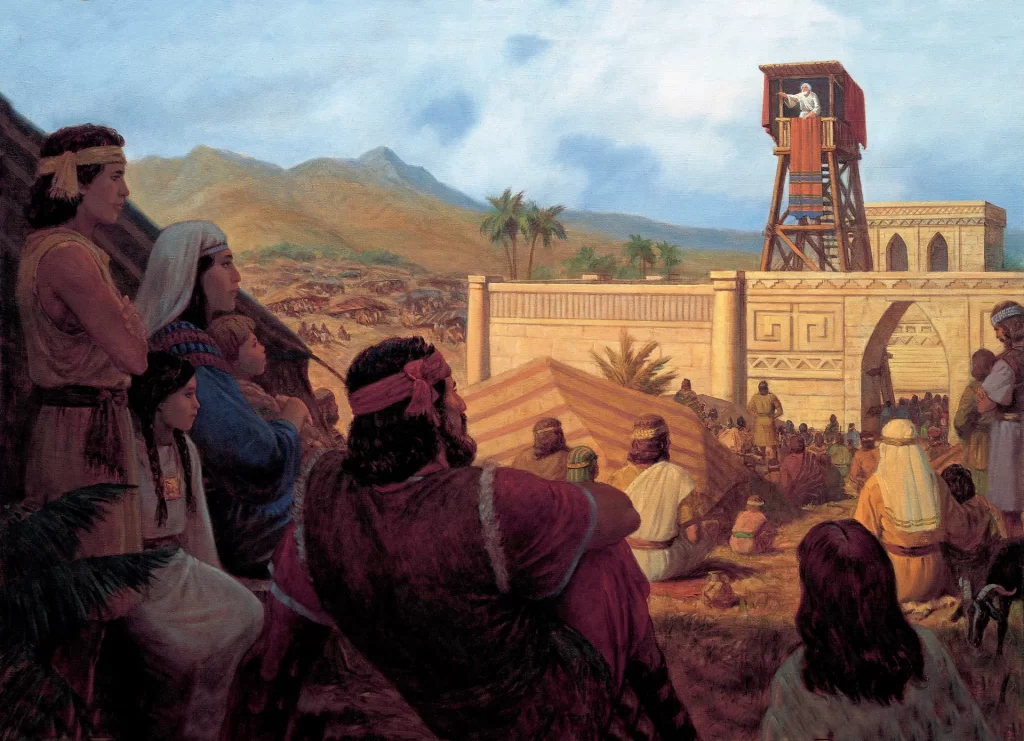

Preaching From a “Tower”

The idea of King Benjamin calling for and building a tower in Mosiah 2:7 is highly anachronistic. Structures like those during the Cane Ridge Revival were built to ensure that large crowds could hear and see the preacher. It wasn’t uncommon for these structures to be built as well as make-shift structures as well.

In Mosiah 2:7, it says: “And he caused that a tower should be built, that thereby his people might hear the words which he should speak unto them.”

This article shows an excerpt from The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement from pages 164-166. It states the following about the Cane Ridge Revival:

Accounts of the meeting refer to the “tent” — a covered lecture platform or stage made of wood located 100 yards to the southwest of the meetinghouse. Based on attendance reports in the thousands for Presbyterian sacraments in central Kentucky earlier in the summer, such structures were necessary since the log meetinghouse had a maximum capacity of 400…One participant counted “seven ministers, all preaching at one time” in different parts of the camp, some using stumps and wagons as makeshift platforms. “

If this isn’t compelling enough, notice the scene in “Camp meeting of the Methodists in N. America by Jacques Gérard. ” Notice the structure in the middle and the individuals on the ground. This is a piece created in 1819 describing a scene that would all too familiar to young Joseph Smith.

LDS Apologetics and Responses

I want to respond to some of the apologetics on this topic ( which you can find here ). In this article from FAIR, much of the debate centers on Grant Palmer’s book and the question of whether Joseph Smith attended specific revival events. However, regardless of whether Joseph Smith attended a particular event, the broader argument still holds: King Benjamin’s speech shares striking similarities with themes, rhetoric, and structures characteristic of Protestant revivalism during the Second Great Awakening.

We Know the Following is True…

In the Book of Mormon, we see:

- Personal Salvation: King Benjamin talks about how everyone needs to repent and rely on God for salvation, much like revival preachers did (Mosiah 4:5-12).

- Emotional Language: His speech uses strong, emotional words to move his listeners, similar to the vivid language used by preachers during the 1800s (Mosiah 4:2, 4:12-13).

- Covenant-Making: Just like in revival meetings, the people make a promise to follow God (Mosiah 5:5).

- Judgment and Preparation: King Benjamin warns about preparing for judgment day, just as revival preachers did (Mosiah 2:38).

- Falling Under the Spirit: People “fall under the spirit” in response to his speech, much like the emotional reactions seen in revival meetings (Mosiah 4:1-2).

- Preaching from a Tower: King Benjamin uses a platform to speak to the crowd, just like preachers used towers or stages in revival meetings (Mosiah 2:7).

In short, King Benjamin’s speech resembles the Protestant revivalist sermons of the 19th century more than ancient Jewish traditions, suggesting the Book of Mormon may reflect the religious environment of Joseph Smith’s time rather than ancient history.